By Canoe Through the Great Lakes

Through the early years of his life as a fur merchant, John Jacob Astor was his own agent at the frontier trading stations, where he made arrangements for the delivery of large quantities of furs. These posts were not always reached by tramping through the wilderness. At least a long stretch of the journey was by canoe.

He traversed the Ottawa and the Great Lakes with Ontario voyageurs, who were a hardy race of men, with a large share of the romantic in their composition. Many of them were Iroquois Indians or half-breeds, though French-Canadians also possessed great skill in handling the boats.

The voyageurs wore a coat made of a blanket, leather leggings to the knees of their cloth trousers, and moccasins of deer skin. From their braided belts of many colors were suspended their knives, tobacco pouches, and other convenient implements. Their language was composed of a mixture of French, English and Indian phrases.

The voyageurs of French descent retained the gayety and lightness of heart of their ancestors, which appeared again even in the half-breeds. Mutually obliging and kindly disposed, adventures and hardships shared together, seemed to have accentuated their friendship for each other. John Jacob Astor found the good humor of these boatmen unfailing, their patience and courage on long, rough expeditions only surpassed by their love of the camp fire and the full pot; their dexterity with the paddles only exceeded by that of the song and dance, when Dame Fortune threw the faintest opportunity for festivity in their path.

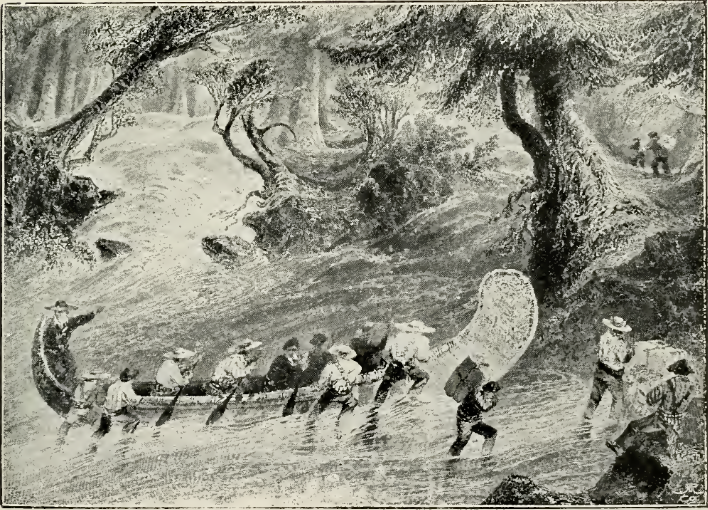

Their canoes, constructed out of carefully selected, thin, but tough sheets of birch-bark, made water-tight along the seams with pitch, were both light and strong, though frail in appearance. The Indians called them a gift from the Great Spirit, and were proud of their ability to paddle their employers swiftly and safely through streams and rapids. A heavier type of canoe, capable of carrying four tons of trading goods, was built for the freight.

Their start on a journey full of peril and daring ventures, was considered a fateful day by the voyageurs. No less so was it for John Jacob Astor, the trader. Even more unknown were the rivers, and the waters of the chaining lakes, to the great venturer.

The employes were tempted to drown their qualms regarding adverse fate, by copious draughts of liquor, but this was forestalled by keeping them busy, and unaware of the exact hour of departure, till the last moment. But there is an inner signal that strikes such hours, and the women and children and dogs knew it, without being told. The human side was ready for a sad farewell, and the dogs for a howling sympathy.

The stout-hearted voyageurs did not allow their spirits to droop for long. The charm of adventure laid hold of them, their spirits swung easily from grave to gay, and cheers followed the boatloads that struck out from shore while at the word of their leaders, the men's voices blended in a song of good luck. The story of the "Three Fairy Ducks" was a favorite, and sung with a lively chorus:

"Behind the manor lies the mere,

Three ducks bathe in its waters clear.

En roulant, ma boule,

Roule, roulant, ma boule roulant.

En roulant, ma boule roulant,

En roulant ma boule."

The dash of the paddles voiced the excitement of the crews.

There were various resting places as the boats went on their way, but one of the most noted was the shrine of Ste. Anne, the patroness of the Canadian voyageur. Here he made confession, and left such relics and votive offerings as he was able. Nor did it seem incongruous to him after these deeds of devotion, to indulge in a grand carouse in honor of the saint, and for the prosperity of the voyage. Whether his gifts were much or little, the voyageur never failed to offer the melody of his voice, the homage of his heart. Thomas Moore, moved by the rythm of the voyageur's song, translated it into:

"Faintly as tolls the evening chime,

Our voices keep tune, and our oars keep time,"

with the refrain:

"Row, brothers, row; the stream runs fast,

The rapids are near, and the daylight's past."

The heavier canoes going to Grand Portage from Montreal, which was a distance of eighteen hundred miles, were manned by eight or nine men to each bark, and could carry besides the baggage "sixty-five packages of trading goods of ninety pounds each, six hundred pounds of biscuit, two hundred pounds of pork, three bushels of peas, two oil cloths to cover the goods, a sail, an axe, a towing line, a kettle, a sponge to bail out water, and gum and bark to repair vessels." Sunk to within six inches of the water, and propelled by strong arms, they covered about six miles an hour, when weather conditions were favorable.

John Jacob Astor, in common with the fur merchants of Canada, imported suitable goods for the trade from England, stored, packed and accompanied them to their destination at the right time. Exchanging trading goods for furs, he in turn packed these and shipped them to England. Goods likely to attract the Indians, and induce a generous exchange in skins, possessed a character of their own. "Coarse cloth of different kinds, milled blankets, arms and ammunition; linen and coarse sheetings; thread, lines and twine; common hardware; cutlery and ironmongery, brass and copper kettles, silk and cotton handkerchiefs, hats, shoes and stockings, calicoes and printed cottons—and in particular, blue beads."—were among these desirable articles of trade. As the red men never closed a bargain, unless they considered they had the advantage, the choosing of acceptable trading goods was very important.

As the boats swept up the Ottawa, though the work was hard, exhiliration increased rather than diminished. One song followed another, changing from rollicking to tender, and then to one of inspirational power.

A characteristic love song of the voyageur's of the early days, freely translated by Mrs Henry Malan, is full of the spirit of the time:

"With a heart as wild

As a joyous child,

Lived Rhoda of the mountain;

Her only wish

To seek the fish,

In the waters of the fountain.

Oh, the violet, white and blue!

The stream was deep,

The banks were steep,

Down in the flood fell she;

When there rode by.

Right gallantly,

Three barons of high degree,

Oh, the violet, white and blue!

'O, tell us, fair maid,'

They each one said,

'Your reward to the venturing knight,

Who shall save your life,

From the water's strife,

By his arms' unflinching might.'

Oh, the violet, white and blue!

'Oh! haste to my side,'

The maiden replied,

'Nor ask for a recompense now;

When safe on land,

Again I stand,

For such matters is time enow.'

Oh, the violet, white and blue!

But when all free

Upon the lea,

She found herself once more,

She would not stay.

And sped away,

Till she reached her cottage door.

Oh, the violet, white and blue!

Her casement by,

That maiden shy,

Began so sweet to sing:

Her lute and voice

Did e'en rejoice.

Like early flowers of spring.

Oh, the violet, white and blue!

'Oh, my heart so true

Is not for you,

Nor for any of high degree;

I have pledged my truth,

To an honest youth,

With a beard so comely to see.'

Oh, the violet, white and blue!"

A beard was evidently a sign and seal of the dashing and brave, and withal, romantic voyageur lover.

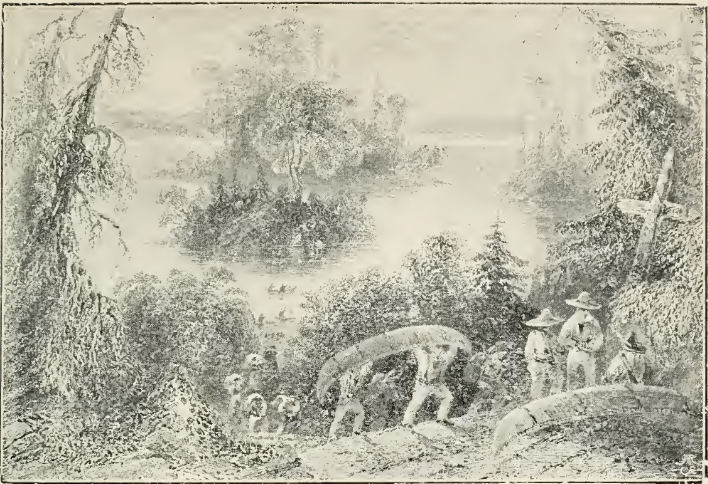

As a portage was reached, the man in the bow jumped quickly into the water, to prevent the canoe from grating on the bottom. Lifting it to their strong shoulders, the bowman and steersman carried it to shore, while the middle men tied their slings to the packages, and swamg them on their backs to bear over the portage. Each act was full of enthusiasm, and performed with the quick deftness of accustomed labor.

The trees were often blazed to show the exact spot where portage commenced. A day's journey might include the climbing of high mountains, and the piercing of dense forests, making the hard trail at times with so little food in their stomachs, that they were constantly hungry.

Occasionally the carrying paths were shorter, and led around waterfalls and impassable rapids, or skirted torrents and precipices. The portages were so fraught with peril that they frequently became burying grounds. Sometimes priests, who had traveled the same hard paths with a chapel on their backs, instead of goods of commerce, had erected an altar beside the way. The birch trees, where the portage struck the streams, were stripped of their bark, for here the canoes were mended.

These canoe trails bore many names, among them a few that bespoke the glory, as well as the hardships of the passage, "the portage des Roses," where the wild roses grew; "the portage de la Musique," where some rippling stream sung as it danced along, were among the former. One of the well-known paths from Montreal skirted an oak grove, and led across a flooded meadow. Father Dablon, who traveled it in common with the voyageurs, said "the path led through paradise, but was as hard as the road to heaven."

When the weather was calm and serene, and the paddles dipped in exact time to the voyageur's melodious strains, John Jacob Astor found his journey in search of furs full of pleasureable sensations, followed by thrilling exercises of mind which were the traders' portion, as they ran the rapids, either with boats lightened according to the depth of the water—while part of the goods went by land—or when they took the risk and ran down the whole load.

There were places of great danger on the Upper Ottawa River. Dr. Bigsby, an early traveler in this section of the country, tells of a ravine or chasm in which the Ottawa ran, which "is so narrow and deep that the sun rises very high before it shines on the water, and hardly at all in winter." He continues: "Many rapids occur, but the most serious is that of Brisson. It is very swift and turbulent. As our canoe turned round and round in it, in spite of all our men could do, the sight of thirteen wooden crosses lining the shore, in memory of as many watery deaths, conveyed no comfort to my mind."

"Deep River" and the "Narrows of Hell Gate," came in for somber stories, and superstitious awe and dread. Running rapids, injuring and mending canoes, building camp fires, distributing provisions, quieting discontent, holding the enthusiasm until success was won, were all a part of John Jacob Astor's experiences on these long and hazardous trips.

Camp fire stories were full of actual tragedies as well as superstition. Sometimes a voyageur pointed out the exact spot where a fur trader had been swept to his death by a fierce eddy. One tale of danger and death was matched by another, and these stories told on the edge of a dense forest usually culminated in actual ghost stories, particularly that of Wendigo, a spirit who had been condemned to wander over forest and stream because of crimes committed, who occasionally took on the form of an outcast, and sought for human food among the trader's party. With such superstition deeply seated, each day's journey was sure to close at sunset, lest unluckily, the crew be met by this sinister apparition.

John Jacob Astor was forewarned in somber detail of the danger of rapids, whirlpools, and deceptive currents along the Ottawa, and the more mysferious dangers that haunted the shadowy woods. Yet the heart of the forest had its pleasant surprises, as well as fearsome stories. Br. Bigsby was surprised one day to meet along a rocky portage, a young lady, a genuine nymph of the forest, with no hint of disaster about her. He tells of the unexpected meeting in an interesting way:

"I had a great surprise at the portage Talon. Picking my steps carefully, as I passed over the rugged ground, laden with things personal and culinary, I suddenly stumbled upon a pleasing young lady, sitting alone under a bush in a green riding habit, and white beaver bonnet. Transfixed with a sight so out of place in the land of the eagle and cataract, I seriously thought it was a vision of:

'One of those fairy shepherds and shepherdesses, Who hereabout live on simplicity and water cresses.'

Having paid my respects with some confusion, (and very much amazed she seemed), I learned from her that she was the daughter of an esteemed Indian trader, Mr Ermatinger, on the way to the Falls of St. Mary with her father, and who was then with his people, at the other end of the portage; and so it turned out. A fortnight afterward I partook of the cordialities of her home, and bear willing witness to the excellence of her tea, and the pleasantness of the evening."

John Jacob Astor traveled hundreds of miles by canoe and portage in these journeys—trips that involved great daring and supreme hardships—between his start at Montreal, and his arrival at the copper rocks of Lake Superior. He worked with his men in the removal of bales of goods, before the canoes were taken over the rapids; his practiced eye pierced the depth of the water, as the boats were lightened to exactly the right weight to avoid the rocks beneath the surging waves. Yet paddling against cold head-winds, a boat would sometimes strike a stone, and nearly upset, or tear a dangerous square from her bottom. In these cases, men and goods were all in danger of sinking beneath the waters before they reached shore, when only the energy and skill of the French voyageurs and Indian half-breeds saved goods and provisions before the boat sank.

These were journeys full of tense courage and hair- breadth escapes, of muscles strained to the utmost over successive portages, or one of unusual length. What wonder that the songs in the quiet waters smoothed the way, and heartened the voyageurs for the next hardship!

That John Jacob Astor accomplished the feat of shooting the dashing rapids of the St. Mary's River in a birch-bark canoe, with a couple of Indians, would suggest that pure love of adventure sometimes stirred the great merchant's heart, and fired his brain.

Skirting the north shore of Superior was part of these canoe journeys, and though near their destination, danger attended them to the close. There were trading posts along the shores, where the fur trade was at its height, but the waters of the lake were deep and cold, and often stirred by angry winds, while its rocky banks offered fresh risks.

Most carefully the voyageurs picked their way along, knowing well that a man who fell into the icy lake was seldom rescued, and a boat split open on the jagged rocks beneath the water, meant loss and death.

Lake Superior had its weird legends, too, of Inini-Wudjoo, a great giant, and of the hungry heron who devoured the unwary.

Grand Portage was the goal of the Montreal voyageurs till the end of the century. Here great encampments were made on the grassy slope around the walls of the fort, and the surrounding water was alive with canoes. Here the east and west met—the couriers of the wild western woods, and the courageous boatmen of the east. Adventure was in the air. There were tales of separation and meeting; narration of weeks of hardship and daring encounters wdth wild animals; of hunger, and of the full kettle over the camp fire. But most of all, vast packs of peltries changed hands, and hundreds of laboring men were engaged in making and pressing bales of furs, while the clerks of the fur companies were occupied in marking them.

We have no evidence that John Jacob Astor was at Grand Portage on July 4th, 1800, but Daniel Harmon, a young New Englander, a clerk of the Northwest Company, gives a spirited account of events there on Independence Day, similar to those other traders must have seen during their own visits to the fort. Harmon says:

"In the daytime the natives were permitted to dance in the fort, and the Company made them a present of sixty gallons of shrub. In the evening the gentlemen of the place dressed, and we had a famous ball in the dining room. For music we had the bagpipe, the violin and the flute, which added much to the interest of the occasion. At the ball, there were a number of the ladies of the country, and I was surprised to find that they could conduct themselves with so much propriety, and dance so well."

While the voyageurs and wood-runners loaded and unloaded, they feasted and contended; the air was rife alternately with disputes and jocularity. John Jacob Astor and his fellow traders carried heavy responsibility amid the general feasting and sociability. For them it was not only a venture of wind and tide, of fierce rapid and tedious portage, but a venture in skins and peltries, whose number, selection and price, whose suitable handling and packing, and safe convoy back over the hazardous route, was to mark the measure of their success in the fur business.