The Astorhaus

From 1820 to 1822, and from 1829 to 1834 Mr. Astor resided in Europe. Soon after his arrival on the continent, he made an extensive tour of Germany. Here was the land of his birth, and the home of his boyhood, and he was drawn, perforce, to his native village of Waldorf.

The little town belonged to the old, old world. It had not changed in these years that had been full of opportunity and achievement for one of its children. The way thither was the same. There were the long plats of vegetables and clover, and the beautiful wild flowers which John Jacob Astor remembered as a boy. The women were still hoeing in the fields beside the men, making bright spots in the landscape with their red skirts; the carts were still drawn by cows.

There were, also, the same red tiled roofs, with small windows like eyes among the tile; the narrow streets, with the stones laid from doorstep to doorstep; the old street pumps nine feet high, unto the top of which no child could grow, though he might one day reach the handle; and the old cemetery, where his mother had been buried in the lonely years of his childhood.

All of it appeared to John Jacob Astor as if he had left it but yesterday. The old church brought back that pivotal Confirmation Day, when he was fourteen,-and life seemed to turn backward upon itself, offering no hopes for the future to the boy aquiver with the desire to go forward.

There were the roads he trod as an unwilling assistant in his father's business, and the lanes where he carried the little ones of the family, searching for amusement for them, and quietness for himself.

The highway leading out of Waldorf toward the Black Forest, no longer looked like a road of fate,—a pathway of magnificent possibilities, with awe-inspiring distances between,—but simply a stretch of country roadway on which the sun shone, the birds sang, men and women and cows worked, and children called after the stranger a cheerful "Guten Morgen."

It was during the period of Mr. Astor's second stay abroad, that the excavations were made in the mounds of his old playground on the Roman road. It may well be imagined that the revelations of what lay buried beneath the grassy hills found an interested spectator in the old Waldorf boy.

Mr. Astor had already made financial provision for the surviving relatives in his old home, but something of all that this visit meant to the German-American, was later shown in the bequest which gave expression to the thoughts of his heart on his return to his native village.

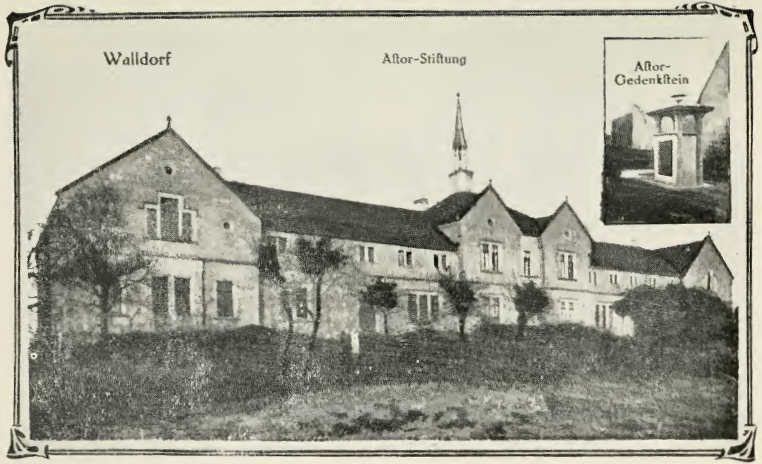

It was not till after his death that the town became aware of the gift of her son. John Jacob Astor had set apart fifty thousand dollars to build an institution for the benefit of the poor of Waldorf. A nephew of Mr. Astor's and one of his executors, appeared in the village one day, prepared to pay over the money to those who were to have the institution in charge. Before night every house in the little town was agog with the news.

As the days passed, it was found that there was to be a Board of Supervisors composed of residents of Heidelberg,—professors from the University and clergymen,—but the real management of the Home was to be placed in the hands of the clergy of Waldorf, the burgomaster, the physician, a citizen named every three years by the Town Council, and the Superintendent of the institution, who must be a teacher by profession.

Considerable time elapsed while the plans were being perfected, and the accumulated interest on the fund eventually went a long way toward building the Home, so leaving the larger part of the bequest to be permanently invested for the support of the institution.

They named it, when finished, the Astorhaus. The two main objects of the Home were, the care of the poor, who, through age, disease, or other causes, were unable to work; and the education and moral uplifting of young people, who were without means. Children needing the care of the Home were admitted at six years old, and from that time until they were fifteen, were trained in habits that would stand them in good stead in after life. The trend of their dispositions and tastes was observed, and each one was taught a trade by which he could afterward earn an honest livelihood. Instruction in agriculture, market-gardening, the care of vineyards and animals were also added, fitting them for these occupations if they showed any bent in these directions. Children of any and all religious creeds were to be admitted.

The boy who had lain awake nights puzzling how he should get his own start in the world, thus smoothed the way to a life-work for many other boys. Nor were the aims of the Astorhaus to be entirely along industrial lines. The blind and the deaf and the dumb were to find succor here, and a nursery for very young children, who had been left destitute, was also contemplated.

The Astorhaus was finally opened on January 9th, 1854, with becoming ceremonies, and continues its beneficent work to the present day. In the chapel of the building, there hangs an excellent portrait of Mr. Astor, and here each year on the anniversary of his death, a commemorative service is held. The boys and girls who have gone out from this institution equipped for life, have had reason to remember with gratitude the boy who had to forge his own hard way, and who turned back during a successful life, to make the road less difficult for their young feet.

It is not strange, that with this village blessing always before his eyes, the Rev. C. W. Stocker, pastor emeritus of the old church, was moved to write of John Jacob Astor:

"Although married to an American lady, and himself an American, so that he could scarcely speak his mother tongue fluently any more, he nevertheless remained German in his heart, and it is said always had a longing for his mother country.

Astor was of medium height, broad shouldered and sun-burned. His eye betrayed a restless activity, and he was accustomed to answer the conversation of others with a melancholy smile; his whole appearance was of a reticent, seriously-minded and melancholy man. He did a great deal of good, saw things in the right light immediately, and was incredibly quick at figuring; so that, in spite of enormous losses which he suffered, he left a large estate at his death.

Few people were as quiet, precise and upright as he was, holding the memory of his friends sacred."

The marked sobriety of which the Rev. Mr. Stocker speaks, was doubtless magnified at this time by physical suffering. Mr. Astor's intimate friends often spoke of his enjoyment of a good joke, though he showed also an undercurrent of sadness.

After visiting Germany, Mr. Astor spent some time in Paris, where General Armstrong, the father of Mrs William B. Astor, had been American minister. In his spare hours during his active business life, he had acquired some knowledge of French, and now in his more ample leisure, he set himself to learn Italian, both languages adding greatly to the pleasure of his travels.

He spent two winters in Italy, enjoying the wonders of art in Rome and Naples, interested in Pompeii, and charmed with the beauties and soft air of Southern Europe. The world of living men also drew his notice, and from some of those who had wielded unusual power in the world of statesmanship and diplomacy, he received marked attention.

He was presented at the Court of Charles the Tenth: and also at that of Louis Philippe; at Naples he witnessed the accession to the throne of young Ferdinand II. He had also the pleasure of meeting Guizot in Paris, and Metternich in Vienna.

These years of foreign residence were not entirelyspent in travel or brief sojourns. Mr. Astor purchased a villa on the Lake of Geneva named Genthod, where he passed his summers reveling in the exquisite beauty of the lake shores, and the clear blue tint of the water, reflecting over again the grandeur of the scenery even to Mont Blanc, fifty miles away.

His daughter Eliza was with him at these times, and together with her husband, a courtly gentleman of the old school, they spent happy summers surrounded by the beauty of the Swiss Lake.

In Europe, as in his adopted country, Mr. Astor drew from his surroundings a wealth of vivid impressions, which he enjoyed at the time, and laid away for future reflection. But the life of the new world had grown very dear to the man who had helped to make it, and he gladly returned to America in 1834.