Homes and Neighbors

On the site upon which the Astor House stood for many decades, John Jacob Astor lived in a large double house for a quarter of a century. This house was 223 Broadway. On either side of him the length of the block, the substantial three-story brick houses were occupied by men who were well known to their day and generation.

Aaron Burr moved from 221 Broadway to Richmond Hill, the same year John Jacob Astor took up his residence in the block, and in this house Michael Paff established his celebrated picture gallery. Two hundred and nineteen Broadway was occupied successively by the brothers, Walter, and Colonel John Rutherford, who belonged to an eminent family connected with the merchant interests of New York. Colonel John Rutherford built his house before the Revolutionary War, and opened the street, though he changed the size and architecture of his dwelling during the yars he was Mr. Astor's neighbor. He had been one of the Colonial Council and a member of the Colonial Assembly, his family intermarrying with the Alexanders and Stevens of Hoboken.

The house adjoining Mr. Astor's on the other side had been the residence of General Moreau when he first came to New York, but for years Alexander S. Stuart, a famous merchant of that day, was Mr. Astor's neighbor, to be succeeded by Cornelius Roosevelt, and later by David Lydig, one of the daring old race of merchants who built up New York.

The father of the last occupant of the house, Philip Lydig, had been a native of Germany of good family, and upon coming to America engaged in the wholesale flour business, with large mills near West Point, and commodious buildings for carrying on his extensive operations in New York.

David Lydig followed his father in the business, owning a house in New York, and a country-seat near West Farms, Westchester County. Country-seats were considered a necessary part of an establishment in those days, and in many cases became valuable property for future generations.

The Lydig sloops sailed between the mills and the city home, and were often taken from the business route to give the friends of the family the pleasure of excursions through the Highlands, the trip sometimes extending as far as Albany.

The enjoyment of these leisurely sloop journeys, with their parties of chosen friends, is to be found in many a diary and letter of the period. The sense of personal hospitality from the owner of the sloop, the genial camaraderie of the Captain and officers, the exchange of wit and humor and the matching of stories between guests, filled these trips with a peculiar type of enjoyment.

The exquisite scenery of the Hudson, unspoiled by modern schemes, awoke enthusiasm along its many miles, as the voyagers sailed near its wooded banks, or watched the wild birds in their flight; lay idle in some shaded cove during the heated hours, or swung forward with the wind in every sail, a dancing boat on the blue waters.

Night often found them sheltered under some guarding bank, a thousand candles overhead; or storm-bound, they dropped anchor in some safe retreat, while they, watched the waters whipped into yeasty foam and curling white-caps in the broad spaces beyond.

One of the greatest charms of these sloop journeys was the visits made upon friends all along the river front. Welcomes were warm from the families of these scattered estates, who claimed each other as neighbors, though miles intervened. Stables full of road-horses, the stages on the post-road, and the private ownership of sloops on the river, over-rode distance for these leisurely folk, as successfully as steam cars and trolleys and automobiles do to-day.

David Lydig was both President and Treasurer of the German Society, to which John Jacob Astor belonged, as Baron Steuben had been before him. He served in various capacities in nearly every prominent bank and insurance company, for half a century.

Just beyond the Lydig home, on the corner of Barclay Street, there resided during the early years of the Astor family's residence here, Richard Harrison, a noted lawyer, and also Attorney General. When he died in 1809, John G. Coster, a retired merchant, bought the house and lived side by side with Mr. Astor for twenty years. When the great financier decided to fulfill the resolve of his young manhood, and build a more elegant mansion than that which, at an earlier period, had excited such marked comment and admiration, he seems to have had but little difficulty in acquiring the houses on this important block of Broadway, upon which he himself lived.

But when he reached the house on the corner, which had been the home of John G. Coster for nearly as many years as he himself had lived in the block, he found an obstacle that even his determination could not surmount. This was the last building lot required by Mr. Astor upon which to build his magnificent hotel, but Mr. Coster could not be prevailed upon to part with it at any price. Money was no object with him, for he was one of the five wealthiest men in New York. Mr. Astor made one offer after another, only to have each in turn declined, the old gentleman positively declaring he meant to spend his remaining days in his old home. In all his previous purchases, Mr. Astor had kept his object a secret, but Mr. Coster's persistent refusal to sell forced him to reveal his purpose.

"Mr. Coster," said he, one day, "I want to build a hotel. I have all the other lots, and I need the ground on which your house stands. With the money I will pay you, you can go up Broadway beyond Canal Street, and build a palace. Now name your price."

Mr. Coster then gave the real obstacle to the sale. "The fact is," he replied, "I can't sell unless Mrs. Coster consents. If she is willing, I will sell for sixty thousand dollars. You can call to-morrow morning and ask her."

When morning came Mr. Astor made the proposed visit on Mrs. Coster, and put his question, as prearranged.

"Well, Mr. Astor," replied the old lady, as if conferring a great favor for no adequate return, "we are such old friends that I am willing to part with my home for your sake."

So Mr. Astor at length accomplished the purchase of the last house and lot on the block, and Mr. Coster took his old friend and neighbor's advice, and built a spacious mansion of granite a mile up Broadway, where he lived the remainder of his days.

Mr. Astor used to tell the story of the whole transaction with great amusement, particularly that part in which the old lady consented to sell him her house at twice its value, under the head of a personal favor. The negotiations, which ended in the purchase of this pivotal house on the block, extended over two years.

When the financier's own dwelling was torn down, he moved to a broad two-story brick house opposite Niblo's, and near his office in Prince Street. Upon the front door of this new abode was a large silver plate, with the simple inscription, "Mr. Astor." By this time the name was so well known that it required no explanatory given-name to distinguish the owner.

Philip Hone writes in his "Diary," under date of April 4th, 1834: "John Jacob Astor has just returned from Europe. He comes in time to witness the pulling down of the block of houses next to that on which I live, where he is going to erect a palais royal, which will cost him five or six hundred thousand dollars.

This racy writer thought that the Astor House would "remain a monument to the great financier for centuries to come."

"The corner stone," according to "The Constellation" of July 19th, 1834, "of this fine building was laid on the 4th instant, at 6 o'clock A. M., in the presence of about a hundred spectators. A box was deposited beneath the stone with a silver tablet in it, containing the following inscription:

'CORNER STONE OF THE PARK HOTEL

Laid the 4th of July, 1834,

The Hotel is to be erected by JOHN JACOB ASTOR.

BUILDERS:

Philetus H. Woodruff, Peter Storms, Campbell

& Adams.

SUPERINTENDENTS:

Isaiah Rogers and William W. Burwick.

ARCHITECT:

Isaiah Rogers.'

"The daily papers of the preceding day—the last number of the 'Mechanics' Magazine,' containing a full portrait of Lafayette—and Goodrich's picture of New York—were also deposited in the box."

The dimensions of the building-to-be, follow, and its style of architecture.

Courtesy of Alfred H. Thurston, the Last Proprietor

of the Astor House

When the Astor House was finished, it was a solid and imposing structure, the admiration of both Europeans and Americans. A short time after its completion Mr. Astor and his son, William B., stood in City Hall Park admiring its magnificence.

"Well, William, what do you think of it?" asked the happy owner of an accomplished dream.

His son expressed his warm appreciation and admiration of this last achievement of his father's.

"William, it is yours," returned the father, to the untold surprise of his son. A few days later the property was turned over to William Backhouse Astor, for "one Spanish milled dollar, and love and affection." There was never any doubt of John Jacob Astor's love and affection where his children were concerned. The Astor House proved to be thoroughly successful, and a gift for which William B. had ample reason to be grateful.

The hotel remained a monument to its builder for the larger part of a century, but it was the life that passed in and out of its doors, both while it bore the name of the Park Hotel, and later of the Astor House, that gave it its greatest glory.

Clay and Webster and Abraham Lincoln were among the names on its registers, oft repeated. The men, whose heart's blood went to the making and saving of a nation, trod its corridors. Those the new world fain would honor were fêted at its hospitable board.

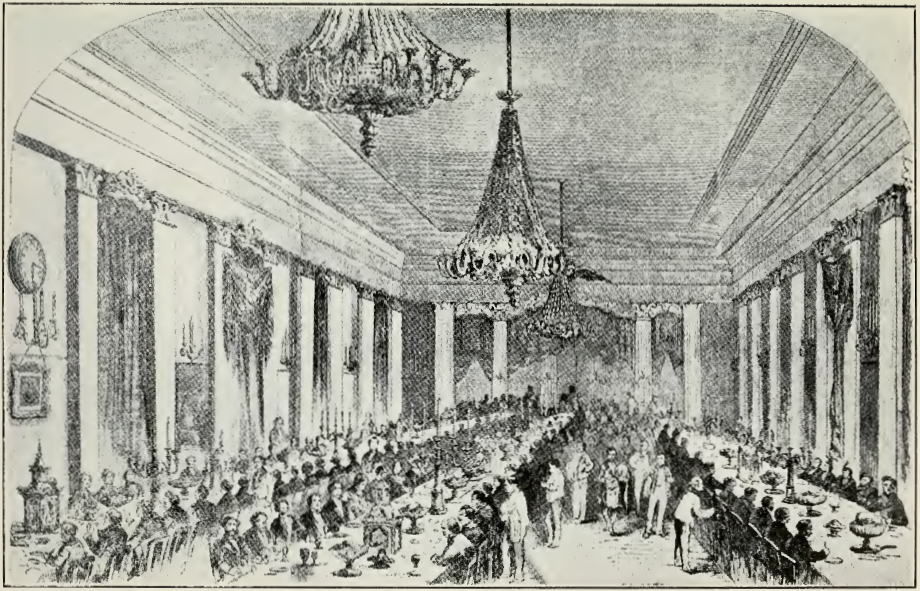

Dinners were given to Jennie Lind and in honor of Burns; to Captain Sands and the officers of the frigate St. Lawrence, by the Common Council of New York, to Governor Louis Kossuth, by the Press; and to many another man and woman famous in the first half and middle of the century. Even to its very last days of existence as a hotel, the Astor House gathered its devotees,—the bridge engineers at a farewell luncheon, at the one table where they had lunched for twenty-five years; and the Municipal Club of Brooklyn, at a farewell dinner; while men and women gathered from many cities to spend the last night in the old Astor House, rich in historic memories intertwined with the nation's growth.

Held at the Astor House, January 25th, 1859

Courtesy of Alfred H. Thurston

One of Mr. Astor's early purchases was a thirteen-acre farm, overlooking Hell Gate. Here he built a handsome country residence, near 88th Street and Second Avenue. Perhaps he remembered, pleasantly, the Todd House on Pearl Street, where he won his bride. The land here had also extended to the water's edge, with an old-fashioned garden upon its banks, and the East River always in sight.

Washington Irving wrote of the Hell Gate home:— "Mr. Astor has a spacious, well-built house, with a lawn in front of it, and a garden in the rear. The lawn sweeps to the water's edge, and full in front of the house is the little strait of Hell Gate, which forms a constantly moving picture"