Landlord and Airlord

When John Jacob Astor, as a young immigrant, first became familiar with the streets of New York, one old writer describes it as a "snug, leafy town, of twenty-five thousand inhabitants."

These had settled for the most part below Courtland Street. By 1800, the city had more than doubled its population, and had grown a mile up the island. The successful fur dealer, of keen brain and clear vision, felt assured that this doubling of population, and covering of space would repeat itself, and acting on this supposition, began to buy real estate.

He had no interest in dwelling houses, or business places, but sought farm land, which often caused his friends to banter him on throwing away money on pasture land, so far from the compact part of the town.

The haystacks of the Bayards stood on a broad sweep of land which is now Lower Broadway, but they were glad to sacrifice good crops, for what seemed to them greater profits, in the shape of two hundred and three hundred dollars a lot, from John Jacob Astor.

John Semlar and his wife sold their East Side farm and ropewalk for twenty thousand dollars, and most of the vast Astor property on the East Side to-day, is built upon the Semlar meadows and cornfields.

Not all of the property Mr. Astor bought was well-cultivated land. Much of it was marsh and rock, and the sellers of those days, considered themselves fortunate in getting a fair price for ground which must, of necessity, prove unproductive. It was a rich opportunity, a real estate boom, in which those wishing to exchange farm or occupation, hastened to offer their land for sale. Mr. Astor's best friends pleaded with him not to risk a fortune already won, in a venture whose success depended on the growth of a city, whose popularity might any day turn into some new channel. Their advice was in vain. The man who had reckoned chances over seas, and across continents, trusted his own acute judgment in this nearer venture.

Property that seemed to the onlookers worth retaining, Mr. Astor parted with. In one instance, he sold a Wall Street house for eight thousand dollars. After the papers were signed, the purchaser seemed inclined to congratulate himself over his bargain at the seller's expense.

"Why, Mr. Astor," he said, "in a few years this lot will bring half again its present value. "Very true," replied the financier, "but now you shall see what I will do with the money. With eight thousand dollars, I will buy eighty lots above Canal Street. By the time your lot is worth twelve thousand dollars, my lots will be worth eighty thousand dollars." This prediction was in the end fulfilled. A portion of Governor Clinton's Greenwich country place, was acquired by the great land-buyer, and is now covered by wholesale buildings.

Medcef Eden and John Cosine both inherited broad acres of farm land, the former in 1797, the latter in 1809. The Eden farm extended on the old Bloomingdale road, now Broadway, from Forty-second to Forty-sixth Streets, stretching in a diagonal line north-westward to the Hudson River. The heir of this valuable estate seems to have frittered it away, and Mr. Astor, improving his opportunity, purchased it.

The farm extended from forty-second to forty-sixth street and from Broadway to the Hudson River

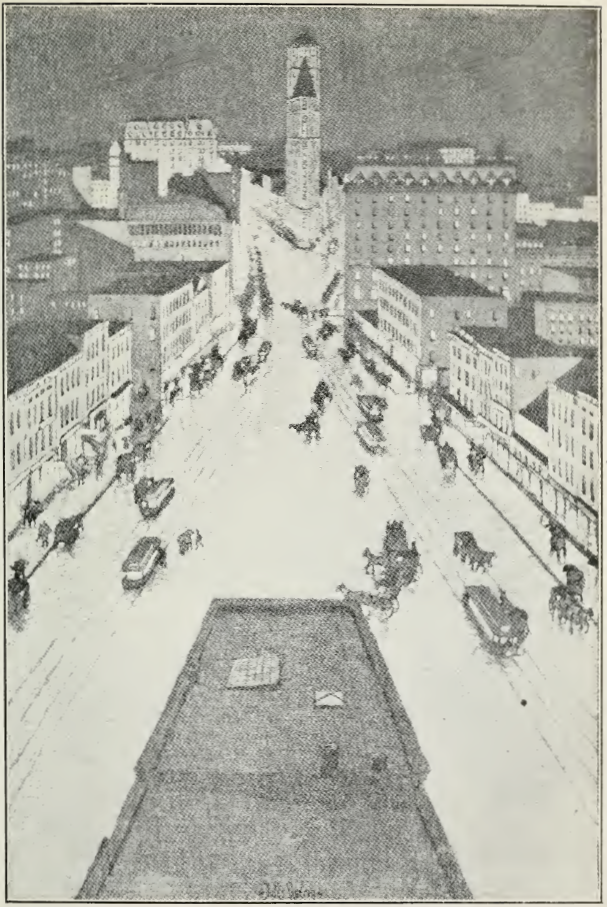

"From the Mural Decoration Edward G. Unitt in the Hotel Astor"

The charming old Eden homestead, with gambrel roof, wide porch, and deep chimney, shadowed by great trees, did not suggest city streets. Neither did the broad, hospitable carriage road, bordered with great elms that led to it, or the sun-kissed pond reflecting the tender greens of spring, or the rich autmn hues, in its quiet depths. City streets through the Eden farm! Only John Jacob Astor could see them! As soon have expected them, some thought, in the first garden that went by that name.

Mr. Astor continued to buy farms. The Cosine farm came into his hands through the chancery courts, and extended from Fifty-third to Fifth-seventh Streets, on Broadway, and westward again to the Hudson River.

John Jacob Astor was fast acquiring land along the river front and backward, equal to that of the great Manors further north. The land, however, was not to be portioned out in leases to small farmers, as that of the Manors, but was to be squared off into city streets, which its purchaser saw in his dreams.

John Jacob Astor always believed in the supreme destiny of New York, and he himself gave it a mighty impetus toward that destiny. Two great Astor Hotels stand on the old Bloomingdale road to-day, and westward hundreds of dwellings occupy the old Eden farm; and hundreds more have been erected on the farm of John Cosine.

Trinity Corporation was land poor in Mr. Astor's time, and many a sale of lots on the church farm were made to Mr. Astor, enabling them to meet current expenses, pay salaries, build parish schools, and care for their poor.

One of Trinity's ninety-nine year leases, covering a third of its great farm, was held by Aaron Burr. Richmond Hill was famous in those days, with the silver-tongued Burr as host, and his brilliant daughter, Theodosia, as its charming hostess. The place itself was picturesque, with wide stretches of wild land, including swamps, rocky ledges and barren commons, lying all the way from Canal Street on to Bloomingdale. But Aaron Burr lived recklessly and extravagantly, and between heavy mortgages, and his quarrel with Hamilton, ruin stared him in the face. The city was moving up toward Richmond Hill, and John Jacob Astor bought the place for one hundred and sixty thousand dollars, thus smoothing for a time the roughness of Aaron Burr's checkered career. Worthless as the purchase seemed at the time, it was one of Mr. Astor 's most valuable investments.

These acquisitions were made with such judgment, as frequently to be sold after a few years, at double or treble the original price. The idea that the great landbuyer never parted with his purchases, is contradicted by the estate books, which record the sale of many plots of land, during the buyer's lifetime, and still more by his descendants, during the remainder of the century. That this was a species of farming that paid, was proved many times over during the succeeding years.

Mr. Astor's land speculations were not confined entirely to the prospective city of New York, for through one of his operations, he acquired the legal title to one third of Putnam County, New York State.

This large tract of land belonged to the estate of Roger and Mary Morris, who having remained loyal to Great Britian during the Revolutionary War, forfeited their right to the property. They fled to England at the close of the war, and the State sold their land to loyal American farmers.

But it appeared that the original owners had only a life interest in the estate; that the property really belonged to their heirs, with all the houses, barns, and other improvements that had been made. Naturally the heirs felt they had some claim which the State was bound to recognize, and after a thorough examination of the papers concerned, by the best legal talent of the day, John Jacob Astor bought the rights of the heirs, in 1809, for one hundred thousand dollars.

Roger Morris was dead, and Mary, his wife, was aged and infirm, and it was not until 1815 that Mr. Astor pressed his claim. The farmers living upon the land, were aghast. The estate covered fifty-one thousand, one hundred and two acres, divided among seven hundred families, who were relying on the titles given them by the State of New York.

Commissioners were appointed by the Legislature to look into the matter, and finding Mr. Astor's claim a wholly legal one, asked for what sum he would compromise. The value of the land was estimated at six hundred and sixty-seven thousand dollars, and Mr. Astor offered to sell his claim for half that sum, but his offer was not accepted.

The case lingered through several years, being brought up again in 1819, when Mr. Astor repeated his previous offer, with interest added, and again no agreement was reached.

Meanwhile the lives of farmers and town's people, with their fear of ejectment, from what they had every reason to consider their own property with a clear title, was not enviable. It was not until 1827 that a test case was tried, in which Daniel Webster and Martin Van Buren stood for the State, and Emmet, Ogden, and probably Aaron Burr, though he did not appear in the trial, for Mr. Astor. Daniel Webster used all his customary eloquence in his client's behalf, but it is said that one sentence, of the opposing counsel: "Mr. Astor bought this property, confiding in the justice of the State of New York, firmly believing that in the litigation of his claim, his rights would be maintained," practically decided the case. The Legislature finally agreed to Mr. Astor's own terms, and he received about half a million dollars from the State. The present owners were secured in their titles, and peace settled over a large community.

John Jacob Astor showed faith in New York as no man had ever done before. He discounted its future as he bought lots, either far north beyond the city limits, or on the east or west sides, where scattered cottages set down in the middle of lots, did not suggest future orderly and well-built streets. Mr. Astor's own faith in the city's future, went a long way toward insuring that future.

The judgment of the shrewdest business man of his day drew others after it, and they in turn, were emboldened to embark upon ventures, that depended for their success upon the city's growth.

Capital from Europe sought investment in New York, and men from all over the United States were drawn to the rising town. Year by year this era of confidence increased, until about 1825, when New York began to take on her metropolitan aspect, and exert an influence abroad as well as at home, an influence which has gathered strength with each passing year. At this time Mr. Astor was a multi-millionaire, and an interest in his ventures and successes attracted the whole world.

It has been said that if this great fortune had been acquired in Europe, it would doubtless have been utilized in "founding a family, building grand mansions, laying out miles of beautiful grounds, posibly buying a title;" but here in America, its mere business use benefitted the people. As New York grew, there was nothing she needed so much as houses, comfortable homes within the means of ordinary people. John Jacob Astor built houses as well as bought land, built them well, and fitted them out with the improvements of the day, kept them in good condition, and asked fair rents.

In the rapid growth of the city, there was an opportunity to impoverish the working men and those in moderate circumstances, through the imposition of exorbitant rents, but the great landlord's course controlled the situation, and the city, and its citizens profited thereby.

Notwithstanding the extent and success of Mr. Astor's other business, the increased value of his real estate operations, was the largest factor in the accumlation of his immense fortune. He is said to have "purchased land almost with a gift of prophecy."

A Part of the Old Eden Farm. After a Drawing by Jules Guerin

Courtesy of the S. S. McClure Company

Though this great German-American financier, did not follow his mother-country in using his wealth to set up a grand family estate, he did import from the old world the idea of leasing his land. The larger part of his vast possessions were neither sold again, nor used personally for building purposes, but leased for periods of twenty-one years, the lessee, after paying a reasonable land rent, being expected to build houses, make improvements, and pay taxes at his own expense.

A satisfactory tenant could generally renew his lease, and so continue in possession of home or business. The system was never popular in the new world, either as exercised between landlord and tenant in the cities, or between Lords of the Manors and the farmers on their great estates in the country. In the latter case it led to the Anti-rent War.

John Jacob Astor, however, was not called upon to meet a war of his tenants. He simply allowed his land to lie idle, until some tenant, forced by its favorable location to rent it for business purposes, set aside his prejudices, and paid the rent asked, renewing the lease at the end of twenty-one years, or leaving the dwellings and other improvements to add to the value of the great landlord's estate. Some of John Jacob Astor's descendents have improved on this old system of leases, and when a lease expires, offer the land with its buildings to the lessee at reasonable terms, before attempting to sell to others.

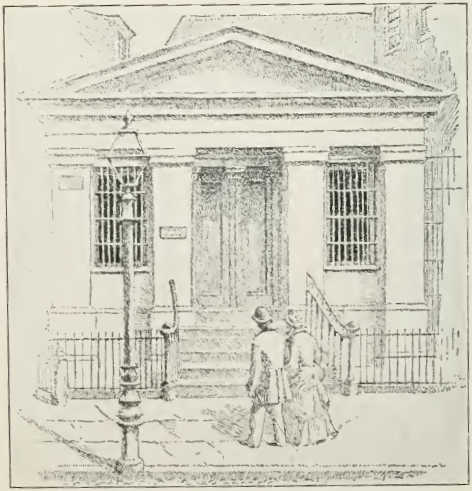

John Jacob Astor and his son, William B., occupied for years the same office, a little one-story building on Prince Street, just east of Broadway Here both gave most careful attention to the mammoth business of which they were proprietors. William B. early became a partner with his father in the fur business, and of real estate was said to have been even a better judge than the elder Astor.

in Prince Street

Situated on the Old Eden Farm

The Thompson farm, the most valuable of the Astor purchases, extending east and west of Fifth Avenue from Thirty-second to Thirty-sixth Streets, and upon which the Waldorf-Astoria now stands, was William B. Astor's purchase.

The elder Astor invested two millions in real estate. At his death the value of his property of this class, was said to be twenty millions. Yet this marked accretion in value was not due to the great landlord's efforts. He simply bought his land in what seemed to him the prospective line of advance of the city. Then he gave the town time to grow.

The city fathers eventually laid out streets through his farms, and occasionally added parks. When DeWitt Clinton, through his project of the Erie Canal, diverted the enormous trade of the West to New York, and with the business, increased the population by hundreds of thousands, one of John Jacob Astor's dreams of New York's future came true.

Homes on Astor land were a necessity, in order to house the incoming multitudes. Railroads and steamships and immigration all made larger and more frequent calls upon it, and the farm lands rapidly became city streets. Grassy meadows that had only been worth hundreds in the hands of their original owners, grew to the value of thousands in the ownership of the great landlord.

Hills where boys had flown kites were leveled with the ground; stretches of land, where ball games had flourished, became city blocks; rippling streams, which the old-time kissing bridges had spanned, and whose transparent depths had mirrored many a love scene, were filled with earth, and made the path of many feet.

So the city grew, always along the surface of the ground, which John Jacob Astor had bought by foot and rod. But stored away in Mr. Astor's tangible possessions, and unsuspected in his realistic dreams, was an inheritance he never guessed.

The projectors of the elevated road and the subway carried the city in great strides up to, and through John Jacob Astor's farm lands; and one morning after the elevator had been proved a success, the old landlord's heirs awoke to find themselves lords of acres in the air.

In 1830, John Jacob Astor was the only man in New York worth a million dollars. In 1900, the Astor estate had risen in value to considerably over two hundred million dollars.