Founding the Astor Library

The circle of literary friends which Mr. Astor had gathered about him, brought a charm and zest into his later years. Halleck's inimitable conversational powers; Cogswell's mastery of his mother tongue, and his wide and varied learning; Irving's warm affection and sparkling humor; and his nephew, Pierre Irving 's eager interest in all Mr. Astor had planned regarding the great Astorian enterprise; the keen intelligence of his own grandson, Charles Bristed, who absorbed, as only a boy can, through known and unexplored channels, the information, adventure, humor and imagination of this rare group of men, all conspired to produce an ideal atmosphere.

Pierre Irving writes of dining at Mr. Astor's at a time when the conversation turned upon ghosts. Several stories were cited, whose reliability had been credited by eminent men. A guest present voiced his surprise that neither Scott nor Dendie, writing of these mysteries, had mentioned the story of Major Blomberg. Two officers had been detailed to sit up with a body in the West Indies. As the night advanced, one officer had passed into an adjoining room, while his companion remained with the body. To the great surprise of the watcher, he saw the corpse slowly rise and approach him, and presently begin to speak. The story told by this visitor from the secret world, was of a great wrong which had been kept secret. He had been permitted to return, that amends might be made. The apparition bade the astonished watcher call his companion, and then told of a secret marriage to a girl in Ireland, who was expecting a child; gave the name of the clergyman who married them, and told how they could obtain evidence. The guest had seen the sworn statement, testifying to the truth of the story he had related.

Mr. Irving took the position that the man was not really dead, and that the wrong rested so heavily on his conscience as to rouse him from a stupor. He ended the serious discussion of the subject by his aggrieved statement, that he, himself, had been hardly treated by the ghosts; that he had made efforts to gain their attention more than once, but always failed.

Mr. Astor added much curious information and many unique experiences to the conversations which scintillated from the group about his table.

But the intercourse of these friends did not begin and end with anecdotes and ghost stories. In these years of leisure, Mr. Astor's still active brain was revolving a new idea. He wished, as he ultimately confided to his son and the circle about him, to express his grateful feelings toward the city in which he had so long lived and prospered, by some permanent and valuable memorial.

Dr. Cogswell urged the founding of a free public library, which was warmly seconded by the remainder of the group of friends. Mr. Astor's decision was promptly taken in favor of this plan. From the time the library was suggested, it formed a double tie between him and his literary friends.

In 1839, Mr. Astor added a codicil to his will bequeathing three hundred and fifty thousand dollars for the library he wished to found, but later, perceiving that this sum would hardly suffice for carrying out the broad schemes already planned, he added another fifty-thousand. About this time the great financier had begun to withdraw permanently from the business world, which gave him greater leisure for plans connected with his benevolent purpose.

Very soon Dr. Cogswell commenced to purchase "curious, rare and beautiful books" for the library that was to be. Mr. Astor placed sixty thousand dollars in his hands, with special view to some libraries abroad about to be offered for sale.

When an invitation to reside with Mr. Astor was again repeated, Dr. Cogswell accepted, "in the hope of advancing the great project" which lay very near his heart. An agreement was reached in which Mr. Astor offered Dr. Cogswell "fifteen hundred dollars a year, and a convenient office in town, his regular business to be working for the library, and an occasional appropriation of an hour or two by Mr. Astor, when he so desired."

Mr. Astor now gave Dr. Cogswell carte blanche to buy books at any time, when they could be had on good terms, if suitable for the library. Dr. Cogswell took up his work in a house adjoining Mr. Astor's, going with him to Hell Gate in the summer, and continuing to be the old gentleman's kindly and sympathetic companion for the rest of his life. As years passed by, Mr. Astor became more infirm, and Dr. Cogswell spent a larger portion of his time with his old friend. Writing from Hell Gate in 1843, he speaks of being provided with every comfort, and for entertainment:—"Every pleasant day we take a steamboat, and while away three or four hours in the inner or outer bay." Dr. Cogswell's devotion to Mr. Astor was reciprocated, not only by the old gentleman himself, but also by the family he had so long been a part of, between whom and himself there was a warm and tender regard.

Many plans were made for the library, both as to the building and the gathering of books. Architects, masons and contractors were consulted. Both officially and unofficially, the project was present in the intercourse between Mr. Astor and his literary associates for a number of years. They planned together, that this should be a cosmopolitan library of reference for scholars, and naturally, in a matter that lay so near their hearts, Mr. Astor's friends were anxious to see the plans materialize before their eyes.

But in the man of great enterprises the blood was growing sluggish. Advancing years and feeble health were producing a natural reluctance to lifting new burdens, and though he was urged again and again, by both Irving and Cogswell to begin the work, whose completion in his life-time they felt would bring him great satisfaction, the donor of the Astor Library evidently believed that the practical labor of founding the institution was for younger hands than his.

During these later years Mr. Astor enjoyed being read to, and found in these discerning friends able and vivid interpreters of the world of books, whose opening vistas were his delight.

In 1842 Washington Irving was appointed minister to Spain. It was his desire that his old friend, Joseph G. Cogswell, should be appointed as secretary of the legation. Just as he had attained his desire, Mr. Astor awoke to what the absence of both of the friends of the library would mean for so long a period. He thereupon stepped in with a promise to immediately go on with the library, and the offer to Cogswell of the position of librarian of that embryo institution.

This change in arrangements was a disappointment to Irving, and a sacrifice to Cogswell, but the library held a warm place in Irving's heart, and he was unwilling to stand in the way of an appointment so eminently suitable. He was also in keen sympathy with the sacrifice Dr. Cogswell was making in the cause of "good learning in the land."

So Washington Irving sailed for Spain with Alexander Hamilton, Jr., as his secretary-,and Dr. Cogswell remained in this country to become the very able and untiring organizer and manager of the Astor Library, and eventually to visit the literary centers of Europe, to make as complete a collection as possible of the books which would meet the needs of advanced students.

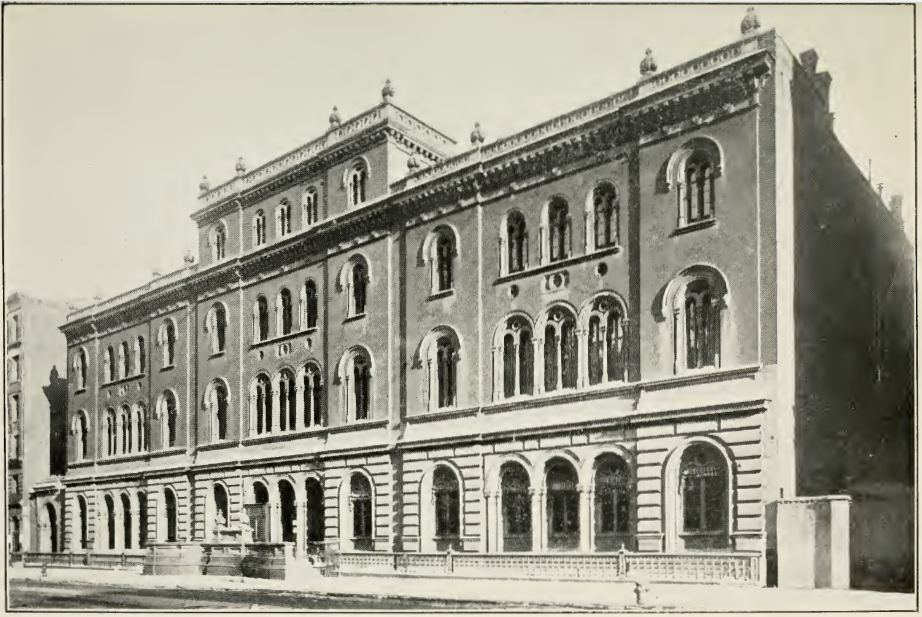

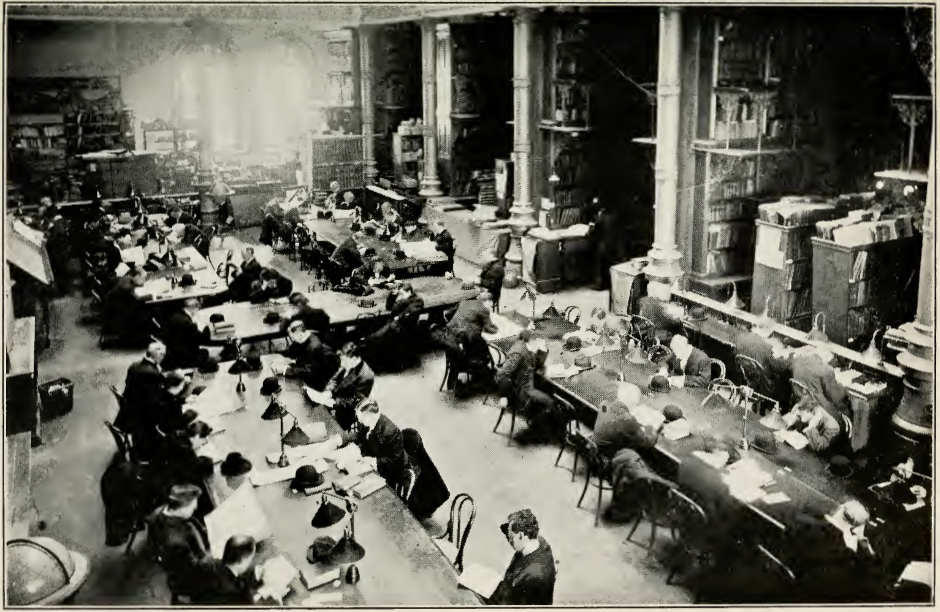

The building was erected in Lafayette Place, New York City, and the Library was opened January 9th 1854, at the same date of the opening ceremonies of the Astorhaus, in Waldorf, Germany. For nearly two generations the Astor Library was a source of reliance and enjoyment to scholars and literary men; both to those who were climbing the lower rounds of the ladder, and also to many who were already famous.

It has been literally "a scholars' court of appeal" and among the earliest of the great city philanthropies for the assistance of whoever would use its benefits. For many years the descendants of its founder continued their gifts to the institution,—in land for additional buildings, in donations and bequests of large sums of money, and in the addition of valuable books and paintings.

By the incorporation of the Astor Library with the New York Public Library during recent years, the Astor Library has not ceased to exist, nor to continue its beneficient work. John Jacob Astor, as one of the earliest of New York's philanthropists, still offers through this great modern library, thousands of valuable books of reference, gathered with utmost painstaking, through the years of half a century. The struggling youth in the world of letters may still find assistance here, through the generosity of the man who was once a struggling youth himself.

The years between Mr. Astor's first thought of an offering of public benefit to the city of his adoption, and the final completion and opening of the Astor Library, were years of seed-planting in the removal of abuses, in help for the needy, and assistance to those who were trying to climb into better conditions. During these years Israel Corse, a Quaker leather-dealer in the "Swamp," was the leader of a devoted band of men who rid New York of the lotteries which were sapping its life. Through their united efforts, the selling of lottery tickets became a crime.

The New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor was organized in 1843, and incorporated in 1848. Five Points Mission had its inception during the same period. The New York Free Academy, which was later expanded into the University of the City of New York, was opened in 1849; the Y. M. C. A. in 1852; the Children's Aid Society in 1853; the St. Luke's Hospital in 1854; and the corner stone of Cooper's Union was laid the same year.

Among the great crowds of the old-world population, which had sought the shores of the "New Land," with hope and large expectations in their hearts, were many who had not met with success. Some could not adapt themselves to new conditions; others were not rugged enough for the rough life of a new country; some had been trodden upon by the fierce striving of others in the race; while a large number had simply not made good, and their children started life as handicapped as their parents before them.

This was the bright dawn of a day when men turned from wholly self-aggrandizement, to consider the less fortunate or striving brother at their elbow,—turned, with what for their time, were munificent gifts in their hands.

All honor to the men who, like John Jacob Astor, took these first steps along a path that has made a half-century glow with a wealth of organized charities and philanthropic endeavors! In comparison with our own time, the gifts may not seem large, but they broke a trail which has opened out into a great white light of beneficent enterprise.