Over the Rockies to Astoria

Wilson P. Hunt, of Trenton, New Jersey, whom Mr. Astor had selected to lead the expedition overland, and locate his intended chain of forts, was a man of decision and resource. Associated with him was Donald McKenzie, another partner, who supplemented Mr. Hunt's qualifications by ten years' service in the Northwest Company, a knowledge of woodcraft and Indian character in the open.

Hunt and McKenzie arrived at Montreal on June 10th, 1811. Both here, and later at Michilimackinac and St. Louis, the influence of the Northwest Company was so strong, that Mr. Hunt found difficulty in obtaining the best quality of men for the journey, but when the party was made up, the voyageurs were proud to include themselves in "a new company that was to eclipse the Northwest."

At Mackinaw they were reinforced by an energetic young Scotch partner, Ramsey Crooks; and at St. Louis, by Mr. Joseph Miller, and an additional number of hunters and boatmen.

They left the latter place in three boats, a Mackinaw barge; a Schenectady barge such as were in use on the Mohawk; and a Mississippi keel boat; all provided with masts and sails to be used if the wind were favorable. The difficulties of their course up the Missouri found the voyageurs at their best. Plying their oars, drawing their boats along shore, or wading in the shallow water, they were patient and fertile in expedient, whipping up their flagging courage with cheerful boat songs.

Four hundred and fifty miles up the Missouri, at Nodowa, where they arrived Nov. 16th, they decided to make their winter camp, and two days later the river froze above them. Here they were joined by another partner, Robert McLellan, a daring Missouri trader, and John Day, a hunter from Virginia. Game was plenty and leaving his party well-cared for, Mr. Hunt made a trip back to St. Louis, where he secured Pierre Dorion, a French half-breed, who had accompanied Lewis and Clark across the mountains, as interpreter, upon condition of their accepting his Indian wife, and two small children as members of the party.

On their journey back to camp they met Daniel Boone, the famous old hunter of Kentucky, who gloried in keeping in advance of civilization,—a sentinel of the frontier. Though in his eighty-fifth year, he had recently returned to his headquarters, the little French village of Charette, with nearly sixty beaver skins as trophies of his hunter's skill. He watched them off from the river bank, no doubt feeling that he would once have been a part of the expedition.

After the rainy season was over at Nodowa, they broke camp and continued their journey. In all they counted sixty men, for they had been joined by two scientists, Mr. John Bradbury and Mr. Nuttall; and also,—as they were several times afterward,—by hardy trappers and hunters, singly or in pairs, who overtook them in canoes or in the depths of the wilderness. These fearless wanderers were glad to join themselves to an expedition which accorded with their own views and type of life.

They breakfasted one morning at the mouth of the Platte River, where they found the frame of a skin canoe, in which a section of an Indian war party had traveled the river. At night the reflection of burning prairies hung in the sky. Once a band of eleven Sioux warriors, stark naked, with tomahawks in their hands, sprang with a fearful yell into their camp. They were on guard, and seizing the intruders found this was a special exploit to cover the disgrace of having failed in war. The Indians were allowed to go, only with a threat of sure death if they were caught in any act of enmity.

Moving on, Mr. Hunt's party camped at Omaha, a village of eight lodges, consisting of tents of buffalo skins painted red or yellow, and adorned with figures of horses, deer and buffalo,—and sometimes human faces. In writing to Mr. Astor at this stage of the journey, Mr. Hunt reported that "the Indian tribes along the river are at continual war with each other, in its most blood-thirsty and cruel forms."

Mr. Hunt pressed forward as rapidly as possible, that they might pass quickly through the danger belt, where they were continually informed that warlike Indians were waiting near at hand to oppose their progress. They avoided the banks of the streams, and hunted only on the islands. On one of these they killed three buffaloes and two elks. It was May now, and the prairies were carpeted in brilliant colored flowers, while the buffalo, elk and antelope had woven paths among the trees and thickets, resembling highways.

A month later they discovered Indian spies on a bluff, who galloped off to give notice of their presence. There proved to be six hundred savages in all set on preventing their approach. To pass them was impossible, and Mr. Hunt's party prepared to fight, but the loading and discharging of two howitzers mounted on the boats, had a marked effect among the Indians.

Buffalo robes were raised above the red men's heads, then spread on the ground as an invitation to a conference, and what had looked like a bloody affray ended in a peace council with the Sioux. Mr. Hunt's party explained their intentions to join their brothers, at the great salt lake in the west. Presents of corn and tobacco softened the chieftain's heart, and he, in turn explained that they were opposing the passage of supplies and ammunition to tribes with whom they were at war.

Another time, having refused some Indians presents, to the extent they claimed, they were again looking for attack, and dividing the party, took the channels either side of a long island, in order to watch the opposite banks. Mr. Hunt's party, finding themselves far up a narrow channel in shallow water, turned back. At this moment two pistol shots, the signal of danger, sounded from the opposite stream, and they discovered the bluffs over their heads, and opposite the end of the sand bar which they must pass in returning, filled with warriors armed with bows and arrows. The situation was critical in the extreme. The opposite party, who had progressed much further up their channel, knew the danger would be upon their comrades before they could reach them.

Mr. Hunt's company having no alternative, dauntlessly approached the point of danger, and to their surprise, the Indians threw away their weapons and plunged into the water, crowding around the boat and trying to shake hands. The relief was immense, to find these Indians the friendly Arickaras, Mandans and Minatarees out against the Sioux. Again the peace pipe was smoked, the Indians offering assistance when their village was reached.

As the adventurers advanced, the broad wastes were more and more alive with herds of buffaloes. Sometimes they moved in long processions, and sometimes gathered in groups. At times the shores were lined with the great animals, and many crossed the streams near enough for the marksmen to reach them with their guns. Besides the buffalo there were many deer, gangs of elk, and troops of graceful antelopes.

John Day caught an antelope by lying down flat in the grass, with his handkerchief waving gently from the end of his ramrod. The antelope drew curiously nearer and nearer, until within range of Day's rifle; then his fate was sealed.

Arriving at the village of the Arickaras, they found preparation under way for a council. Mr, Hunt stated again their purpose in traveling through the country, and asked for horses with which to pursue their journey, offering generous payment in goods. The left-handed chieftain promised friendship, but said they had not the number of horses to spare. Whereupon, Gray Eyes, another chief, declared he could supply Mr. Hunt with all the horses he might want, for if they lacked the requisite number, they could easily steal more.

Horses were put through their paces, and the Arickaras rode about showing their dexterity and horsemanship. When a horse was purchased by the whites, the tail was cropped as a mode of distinguishing ownership. A victorious war party returned with scalps while the sale was going on, and there was wild exultation among the Indians. Arraying themselves in paint and feathers, and embroidered buffalo robes sometimes fringed with the slender hoofs of young fawns, they celebrated the victory with intense excitement, mingled with weeping and wailing for those who had fallen.

Some of Mr. Hunt's men having listened to the stories of the trackless desert, the lack of food and water, and the Indians lurking in the defiles of the Black Hills, beyond which rose the stern barriers of the Rockies, lost heart and prepared to desert; but the plan was discovered and frustrated.

They had only been able to purchase eighty-two horses from the Arickaras, and set out with most of them laden with Indian goods, beaver traps, ammunition, Indian corn and other necessities. Each of the partners and the interpreter were mounted, but the men were forced to travel afoot. An interpreter for the Crows, a thievish tribe who infested the skirts of the Rocky Mountains, was discovered in a lonely hunter, and thus equipped the party set out.

They had been advised to take a more southerly route than that of Lewis and Clark, and directed their course first toward the south, and later toward the northwest, in order to avoid the Blackfeet Indians, a ferocious tribe, who put to death all white men who fell into their hands.

Traveling over immense prairies, they reached what they called the "Big River," and camped there several days, to lay in a supply of buffalo meat; and were also able to buy some extra horses from friendly Cheyennes.

An intrigue was discovered headed by the Crow interpreter, who was planning to steal large amounts of trading goods and horses, and join the Crows in the mountains; consequently a close watch was kept on both interpreter and men. Pierre Dorion and two others who were lost for days, in spite of the great signal fires built to guide them by columns of smoke. They came into camp at last, weary and bedraggled. About this time Mr. Hunt won over the interpreter to the Crows, by giving him permission to join that tribe when they came across a party of them, and offering him horses and goods when he left them.

At the edge of the Black Hills they found black-tailed deer and big-horns abounding, and sometimes discovered themselves to be in the haunts of the grizzly bear. Both Indians and whites considered the grizzly big game. John Day shot one of these fierce animals, but another poor fellow had a different experience. He was a poor shot, and after much practicing at marks, had killed a buffalo, to his joy. Returning to camp with rare bits of its meat to prove his victory, he found himself chased by a grizzly. Dropping the meat he ran at break-neck speed. But the bear ignored the meat, and kept up the chase until the hunter was almost overtaken, when he had the good fortune to reach a tree, which, dropping his rifle, he hastily climbed, and the grizzly took up his watch beneath. All night long the hunter held to his cramped position, supremely thankful when daylight came, to find the enemy gone. His return to camp was not what he had expected, but still had its compensations.

They traveled toward the mountains over a rough and rugged Crow trail through the hills, where they found neither water nor game, and lived mostly on a very small allowance of corn meal. After long tramping, a stream was hailed with devout thankfulness as were also the buffaloes on its banks. For days they directed their march toward a high mountain which proved to be one of the Big Horn chain, one hundred and fifty miles away.

The interpreter to the Crows led them through the mountain trail, and although the weather was frosty and the path rugged, they found grassy glens and sparkling brooks, as well as berries and currants by the wayside. They ran across a whole party of Crow Indians going their way, men, women and children all mounted, and for a time were forced to travel together. In the end the Crows outstripped the adventurers, and they were glad to see them disappear, accompanied by the interpreter.

Once a small party of Flatheads and Snake Indians became their guides for a couple of days, camping near them at night, and joining them in the hunt the next day. They crossed and recrossed the windings of the Wind River for eighty miles. Turning toward a stream to the southwest,—hoping to find buffaloes on its banks,—from a high hill the guides pointed out three snowy mountain peaks, above a fork of the Columbia river, which hunters called "The Three Tetons." This announcement was met with great rejoicing, and Mr. Hunt named the peaks the "Pilot Knobs," since they were to become their guides for some time to come.

Within the next few days they struck a branch of the Colorado, called the Spanish River, abounding in geese and ducks and signs of beaver and otter, and on one of its small tributaries found the last of the buffalo herds. Camping here, they hunted and jerked meat for five days, since this would probably be their final supply until they reached the fish of the Columbia. Here they saw Snake Indians killing buffaloes with arrows. Coming up with them, they were able to buy both dried meat and beaver skins from them, and make arrangements for future trade in peltries.

On the 24th of September, they drew near to the "Pilot Knobs," having reached the heights of the Rocky Mountains, and were overjoyed to have their guides point out to them, a little later, the Lewis or Snake River in the distance, the great south branch of the Columbia. On reaching this stream they felt the harder part of the way was covered, and from now on they would be on the home stretch, but they little guessed what was before them.

This stream was joined by one of greater width and swifter current, which they called the "Mad River." Here it was decided they would change horses for canoes, part of the men being detailed to fell trees of sufficient size for canoes, others to march along the stream for several days and examine its navigable possibilities.

At the head-waters of the Columbia, Mr. Astor's plans for trapping began, and trappers were paired off and supplied with horses, provisions, traps, arms and ammunition, with which they were to trap for months on the neighboring streams, bringing their collections of peltries to the mouth of the Columbia, or any intermediate post which might be established. To the surprise of all, Mr. Miller joined one of these trapping parties.

Finding the Mad River unnavigable, they were advised by their guides to make for the post established the previous year by Mr. Henry, of the Missouri Fur Company, on an upper branch of the Columbia. Two Snake Indians guided them to the abandoned post, over an intervening ridge of mountains in the face of four days' wind and snow. They gladly took possession of the deserted log huts, which Mr. Hunt determined to make a trading post.

Ten days later, on the 18th of October, they had completed fifteen canoes and the party embarked, leaving their horses in charge of the two Snake Indians with rewards for their care. The tributary on which they started out ran into the broader Snake River, which very soon was full of boisterous rapids, running beneath steep precipices. Sometimes they were obliged to pass their canoes down cautiously by a line from the perpendicular rocks. They had reached an unknown wilderness of vast mountains, unexplored by white men, with no wigwams on the banks and no canoes on the streams.

The solitary beaver proved the undisturbed character of his surroundings, by choosing his home along the route they traveled. The party had covered two hundred and eighty miles before they began to run across small bands of Indians, who fled at their approach. The voyage became even more rough. One of the canoes struck a rock, split and overturned, with the loss of the steersman, one of the most competent of the Canadians. This catastrophe cast a gloom over the whole company.

They had now arrived at a terrific strait only thirty feet wide, between ledges of rock two hundred feet high, the compressed river whirling and boiling in a great whirlpool. The adventurers gave it the name of the "Caldron Linn."

Exploring parties were sent out to examine each side of the river, and one of the companies trymg to run the rapids, lost all four canoes and their equipment. There were now only five days' provisions left, and it was decided to divide the party. McLellan, and Reed one of the clerks, each with a few companions, continued further down the bank of the river; Mr. Crooks, with five others, retraced their steps toward Fort Henry. If the latter party did not meet with friendly Indians or provisions sooner, they intended to go back after the horses; Mr. McKenzie with five men moved northward, in hopes of finding the main stream of the Columbia. If they found adequate help for the whole party, they were to return. If not, they were to shift for themselves and meet at the mouth of the Columbia.

Meanwhile the thirty members of Mr. Hunt's party left behind, turned their attention toward obtaining provisions, which were principally beaver in very small numbers. They also set to work to make nine caches, in which to hide their baggage and merchandise. Before these were completed, Mr. Crooks' party and two of Reed's men returned, having found that they could not reach Fort Henry and return in the course of the winter, and that the river was impassable. With their several avenues of escape closing about them, they gave the place the name of the "Devil's Scuttle Hole."

They decided to set out immediately on foot. A vast tractless plain destitute of food or water, lay ahead of them if they abandoned the river, and they agreed to keep along its course. Their provisions, consisting of Indian corn, grease, portable soup, and a small amount of dried meat, were getting very low, yet with their blankets, ammunition, and trading goods, amounted to twenty pounds for each man.

Mr. Hunt, with eighteen men, besides Pierre Dorion and his wdfe and two children, kept to the right bank of the river, while Mr. Crooks and his party took the left. The way was so hard and precipitous that it was days before they could get down to the water-side, and their suffering was intense.

Once Mr. Hunt's party met two Shoshoni Indians, whom they persuaded to take them to their camp, which they found to be tents of straw, looking like haystacks. The women, frightened at the white men's appearance, hid their children under the straw, and Mr. Hunt entering one of the tents, perceived the bright eyes of the papooses peering out at him.

They continued to meet small bands of Indians, from each of which they bought one or two dogs and a little dried meat, all the Indians could spare from their own scanty winter supply. Once they dropped down thirty miles on a smooth current, but the waters became turbulent again, and they resumed their rugged path.

Mr. Hunt made every effort to purchase a pack horse to relieve his men but failed, until a battered tin tea-kettle closed a bargain with an old Indian. A little later their leader was fortunate enough to purchase a horse for his own use, for a tomahawk, a knife, a fire-steel and some beads.

In an evil hour they took the advice of some Indians and struck inland across the prairies, only to meet the most intense suffering for lack of both food and drink. When their thirst seemed past endurance, a merciful rain fell in the night, and the men eagerly scooped up the water from the hollows in the sand. After traveling thirty-three miles the next day, they had nothing for supper but a little parched corn. Again they met Indians and bought a dog and a little fish, and "fared sumptuously," but the Indians could not direct them further than to tell them that the Columbia was still far off. On the 27th of November, the river they were following led them into the mountains, through a rocky defile. Before entering this defile they were able to buy two horses for a couple of buffalo robes, from a party of Indians. Traveling on with difficulty, sometimes fording icy streams, they faced snow storms and waded through snow up to their knees, unloading the horses to get them by narrow places.

Meeting neither Indians nor game, they were compelled to kill a horse. "The men found the meat very good," Mr. Hunt wrote Mr. Astor, "and, indeed, so should I, were it not for the attachment I had for the animal." A black-tailed deer, a beaver, and another horse each tided them over a starving time.

Pinched with hunger, they struck camp in a wild snow storm, their provisions entirely gone. Fortunately they succeeded in finding a group of pines. Felling these, they made huge fires and once more killed a horse to appease their hunger. They had now traveled four hundred and seventy-two miles since leaving "Caldron Linn."

On the 6th of December, they discovered Mr. Crooks' party on the opposite side of the river asking for food. A kind of canoe was made of the skin of the horse partaken of the night before, by distending the hide with sticks or thwart pieces. A Canadian crossed with a part of the horse meat, bringing Mr. Crooks and the Canadian, LeClerc, back in a starving condition. This party had met more vicissitudes and eaten even less food that Mr. Hunt's.

Turning back in despair, they had discovered Mr. Hunt, who decided to retrace his steps to the last Indian camp they had passed, hoping to buy horses for food. Upon his refusal to leave Mr. Crooks behind in his weak condition, all of Mr. Hunt's party, except five men, moved on. All day Mr. Hunt and his companions traveled slowly without eating, at night making a tantalizing meal of beaver skin.

Overtaking the advanced party, they all came in another day to an Indian camp, where many horses were grazing. The Indians fled, and Mr. Hunt's party lost no time in killing, cooking and eating a horse, and sending meat by horse-skin canoe to Mr. Crooks' party on the opposite bank. Enough trading goods were left in the Indian lodge to amply pay for the horses they had taken to prevent starvation.

They found a camp of friendly Shoshonies on the little stream where they had previously camped, who sold them a couple of horses, a dog, and some dried fish, roots and dried cherries; then invited the whole party to winter with them, though they were unwilling to provide a guide for the trail over the mountains.

Mr. Hunt felt it would be certain death to take his party over the mountains without a guide, but to remain where they were after so long a journey and so great an expense, was 'worse than two deaths." He taunted the Indians with lack of courage and tempted them with a gun, pistol, three knives, two horses and a little of every article they possessed, until one of them offered to be their guide.

John Day was unable to travel, and Mr. Crooks remained behind with him, being provided with a share of the horse meat. On the 24th of December, having been joined by Mr. Crooks' party, they turned their backs on the Snake River, and struck out westward toward the mountains. They were soon having only one meal of horse flesh in twenty-four hours, and two of the men were so weak they had to be carried, and Mr. Hunt shouldered an extra pack.

Famished and faint of heart, they pressed on until joyfully they came upon an Indian camp, with horses and dogs. Purchasing four horses, three dogs and some roots, they set about getting a good meal, a preliminary feast to the ushering in of the New Year of 1812, which the Canadians celebrated as usual, forgetting for the time the hardships of the way. Excessively toilsome traveling led toward the gap in the mountains through which they must pass. On the other side they found a milder climate, but some of the men were so fagged, they dropped behind. What was the joy of the main party to find an Indian camp in a green valley, with numerous lodges and hundreds of horses, and the information that the Columbia was only two days' march further on.

The stragglers caught up here, and they had news of McLellan's and McKenzie's parties passing down the river. These Indians looked upon the prospect of future trade with great pleasure, and promised to hunt the beaver assiduously. The party struck the Columbia some distance below its junction with the Lewis and Snake Rivers, and were overjoyed at reaching this waymark on their pilgrimage. Dog meat, which they had learned to like, and salmon could be procured from the Indians on the Columbia.

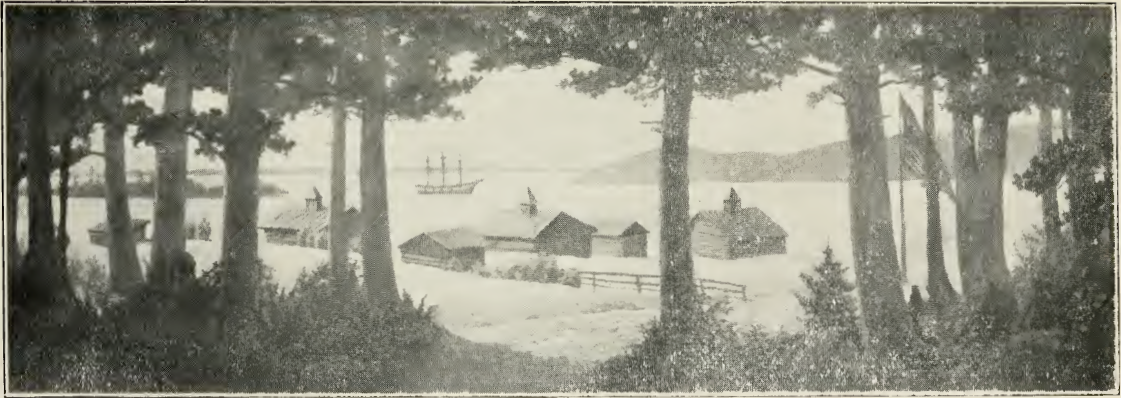

Rumors of a great house surrounded by palisades came to them from these natives, and also the grief at their non-arrival at Astoria. At Wish-ram they found the Indians tricky and dishonest, and needing close watching. Here Mr. Hunt heard for the first time of the loss of the Tonquin, which he only half believed, but it gave him great disquietude. Canoes were obtained at the lowed end of the Long Narrows, and after a windy voyage they came in sight of the little colony of Astoria on February 15th, 1812.

From a painting on the Hudson River Day Line Steamer "Washington Irving"

Courtesy of the Artist, Herbert W. Faulkner

The joy of the travelers after eleven months' wandering in the wilderness, where the sight of an Indian wigwam had been a rare pleasure, can easily be imagined. The route traveled by Mr. Hunt and his party carried them over three thousand six hundred miles, though in a direct line the distance was only eighteen hundred miles.

There were shouts of joy from all the canoes as they crassed the little bay and pulled into land, where all hands hastened down to greet them. The voyageurs hugged and kissed each other, and expressed their pleasure in a noisy fashion. Among the first to welcome the wanderers were McLellan, McKenzie and Reed, whose account of their journey, hunger and thirst and other hardships, were similar to those of Mr. Hunt's party, with the difference that they had overtaken each other, and traveling together in a smaller party, had found it easier to provision all.

They had been saved once from starvation, cowering under a rock in a snow storm, by a big-horn sheltering itself above them under a shelving rock. With the utmost caution, Mr. McLellan, being a very good shot, and the most active of the party in their starved state, had circled above the big-horn till his aim killed it on the spot, after which it was rolled down to the famished group below.

Since they crossed the mountains before the heavy snows, they had reached Astoria a month earlier than Mr. Hunt's party. Thus all were accounted for, except Mr. Crooks and John Day, for whom they felt but slight hope in their weakened condition.

A day of jubilee was celebrated, in which colors were hoisted, guns were fired, and the men who had so long subsisted on horse and dog meat were treated to the best the post afforded, the festivities closing with the usual dance of the Canadian voyageurs at night.