Starting in Business for Himself

About two years after John Jacob Astor's arrival in America, in 1785, he married Miss Sarah Todd, daughter of Mrs. Sarah Todd, a widow, who lived at 81 Queen Street, (now Pearl) not far from George Diederich's, though on the other side of the street.

Young Astor had saved a few hundred dollars, and in 1786, hired a couple of rooms from Mrs. Todd, and set up in business for himself. One of the possibilities of the fur trade in the latter part of the eighteenth century, was, that though it admitted of wide expan sion, it could be entered upon with very small capital.

The young merchant furnished his shop with German toys and knicknacks, and a few musical instruments, paying cash for skins of muskrats, raccoons, and those of other animals, selling them again at a good profit. The proprietor of the little shop worked tirelessly. He could not afford a clerk, and with the assistance of his wife, did all the labor connected with the business himself. Every farmer's boy on the outskirts of the city, occasionally had a skin to sell, and bears abounded in the Catskill Mountains. A large part of New York State was still a fur-bearing country. Even Long Island, near at hand, added her quota of skins. John Jacob Astor bought, cured, beat and packed his peltries. From dawn till dark saw him engaged in some part of the fur trade. His indomitable ardor never waned. He was still upon the lower rounds of the ladder, but climbing.

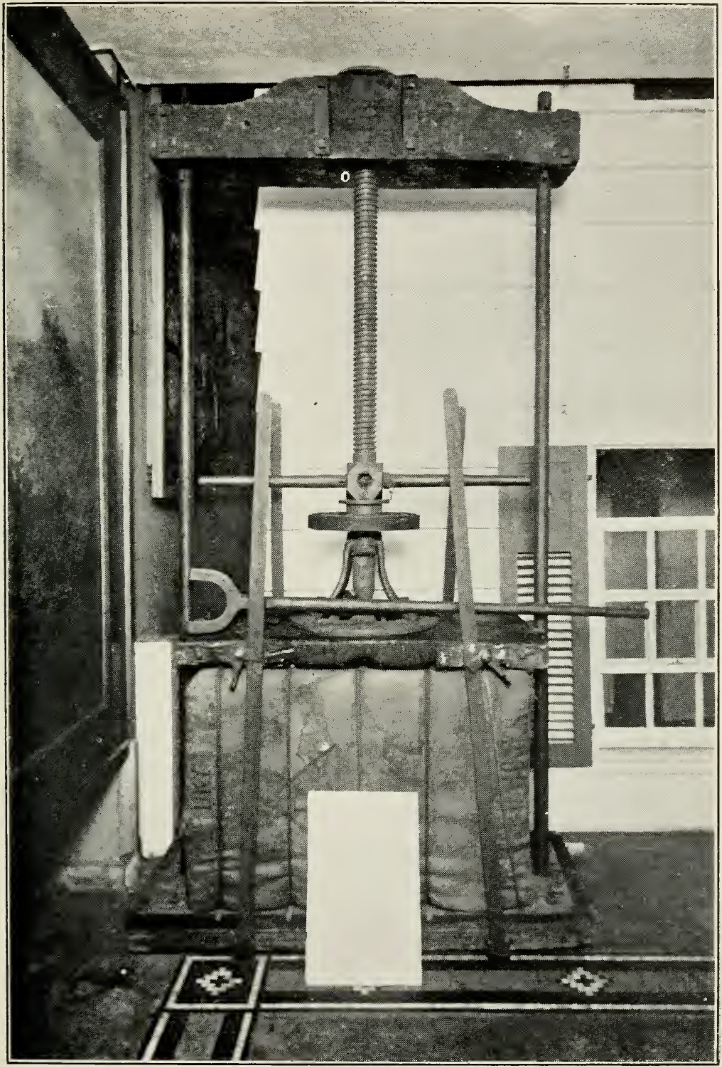

Used in the fur business of John Jacob Astor

Made in 1805

He tells a story of himself at this period. A new row of houses on Broadway was exciting the interest of the city, owing to their unusual size and beauty. As the youthful merchant passed them one day, he said to himself, "I'll build sometime, a grander house than any of these, and in this very street." Yet while he prophesied great things for the future, the present held his unswerving interest and attention.

When the proper season of the year came around, he shouldered his pack and started on his collecting tours. Cakes, toys, paints and trinkets, cheap jewelry and birds, making up a pack of surprising attractiveness to the red men. He is said to have walked over every road, and traversed every Indian trail and bridle path in New York State, in search of furs, climbing mountains, wading or swimming creeks or rivers, if they lay between him and the tents of the Mohawks, Senecas, Oneidas, or other Indian tribes.

He learned to know broad stretches of country, the fording places of rivers and streams, and the positions of the Indian settlements. These Indian settlements were not always stationary. A little colony of tents would be packed up and moved afar between sunset and sunrise; so that the young trader needed not only to iocate his fur-market, but to reckon on flood and drought, full harvests and rumors of war, as well as many another motive, which might cause his journey to any particular point to be in vain.

He formed a partnership with Peter Smith, father of Gerrit Smith, who was at that time a poor youth like himself. Together they tramped all over the ground from Schenectady to Utica, when the latter city was in the making, bartering the goods from their packs for furs at the Indian settlements on the route; the Indians aiding them in carrying their heavy burdens back to Schenectady, or all the distance to the Hudson River. They sold their peltries in New York, and when their stock was exhausted, again penetrated the forests of the frontiers to replenish their supplies.

"Many a time," related a gentleman of Schenectady, "have I seen John Jacob Astor, with his coat off, unpacking in a vacant yard near my residence, a lot of furs he had bought dog-cheap of the Indians; beating them out, cleaning and repacking them in more elegant and salable form, to be transported to England or Germany, where they would yield him a large per cent on the original cost."

After a time Peter Smith settled in the Mohawk valley, opening an Indian trader's store in the corner of his house in Utica to supplement the fur business, but he still sent furs to John Jacob Astor, in New York.

His fearless partner continued his numberless tramps through the wilderness, becoming still more familiar with hills and valleys, the long miles skirting the Hudson, and the shores of the great Lakes. With a clear vision of the future, he pointed out sites of great towns, particularly those of Rochester and Buffalo, one with its harbor on Lake Erie, and the other on Lake Ontario. While he was making these predictions of large and prosperous cities, there were only a few scattered houses at Buffalo, and Indian wigwams at Rochester.

On his shorter excursions into the country collecting skins from house to house, or on his trips up the Hudson, he became a familiar figure as he trod the postroad, stopping at farm-house doors, or passing the time of day with farmers in the fields. Landing a shoulder of skins upon a good dame's neatly sanded floor, was not over-pleasing to a Dutch housewife; but his comings and goings are still remembered at Albany, and Kingston, and Claverack, and many another Hudson River town and village, in the stories passed down to children's children.

At Claverack he found more than a stranger's welcome. The little old knocker on the parsonage door led him into a family circle of friends. Going or coming from his northern trips,—either along the post-road, or by Captain Abraham Staats good sloop "Claverack," which dropped him at Claverack Landing, after which he would make nothing of a tramp of four miles along the beautiful Claverack Creek,—he was pretty sure to stop over for a meal or the night at Domine Gebhard's.

His former townsman had by this time an interesting family of boys and girls, who found Mr. Astor's stories full of delightful thrills. His coming was to them a red-letter day, more entertaining than the most exciting written tales of adventure.

Such a story as that told by the father of General Wadsworth, would find a sympathetic audience in this household. Mr. Wadsworth once met John Jacob Astor in the woods of Western New York, with his wagon broken down in the midst of a swamp. His gold had rolled away into swamp-grass and mud, and he had just saved himself from being swallowed up in the soft ooze. He succeeded in reaching solid ground covered with mud, and possessed simply of an axe, which he had saved from the wreck by continuing to hold it over his shoulder.

Such an event never meant defeat to John Astor, and he imbued his audience with his own dauntless courage, causing them to rejoice with him over his life, and his one possession,—the axe.

Sometimes his stories were of friendly Indians, and newly-discovered collections of furs, of chipping the bark of trees to mark his path through unknown forests, of wonderful speed made in the canoes by Indian paddlers. Or he told of salmon or wild bird, caught by rod or gun, and cooked over an open fire for men whose appetites had the keen edge of long tramping and postponed food.

Tales of shooting rapids in a birch bark canoe gave a breathless thrill to his young listeners; but for the fur trader himself, the number and value of the peltries he had shipped to New York, was the the test of the success of his journey.

John Jacob Astor's broken English was dropped in this household, for the pure German their old teacher had taught both host and guest in the village school in Waldorf. Old times, well-loved people and objects, familiar incidents of the past, were all talked over. The German Reformed Church of New York was a subject of mutual interest, and also came under review.

There were always fellow countrymen crossing the great deep, and something new to tell them at each meeting. On the Livingston Manor, in a place called Taghkanic,—where Domine Gebhard preached four times a year, to a mixed audience of Dutch and German,—he had found families from Baden, near Heidelberg, like themselves. It was also about this time, that John Jacob Astor joined the German Society in New York, a society that counted among its members, during this period and later, Jacob Schieffelin, David Grim, John B. Dash, Sr. and Jr., Jacob Mark, and many others of the prominent men of his own nationality in America, as well as those who were working toward a prosperous future.

It was hardly a strange land when one met an old neighbor from across the sea, on almost any trip abroad. After all, they were both Americans, men who had thrown their loyal all in with this new nation. Domine Gebhard was not only preaching in three languages to five, and sometimes six congregations, but he was also establishing an educational institution, in Washington Seminary, to train the youth of the young nation; and John Jacob Astor, on his part, was building up the commerce of his adopted country.

From stories of hairbreadth escapes from wild animals, and curious intercourse with the Indians, in which the boys were interested; through old-world recollections, and present-day ardent patriotism,—which subjects claimed much of the attention of their elders,- there was probably no more welcome climax for a music-loving German guest, than the Domine's playing, and the melody of his wife's sweet voice, as she sang from a book of eight hundred pages, the songs of the Fatherland and the hymns of John Jacob Astor's boyhood, in his own tongue.